|

I N T E R V I E W Keish of Hard-Ons Pic O'Neill caught up with Keish of Aussie punks Hard-Ons, for a Q and A ahead of their Raglan show on 19th May with 5 Girls, Illicit Wah Wahs and amazingly, Mobile Stud Unit! Keish (drums/vox) founded the band along with Blackie (guitar/vox) from their bedroom aged around 14 yrs old, after Blackie first saw the Sex Pistols on TV, and declared "We're gonna make a band like this!". Initially on guitar, within a year Ray Ahn (bass) had joined and Keish took on drums and singing. Hard-ons roared into life with over 17 consecutive no1 singles on the Australian alternative charts between 1985 and 1993! Dozens of tours of Europe, Australia, Japan, US and New Zealand ensued, where the band sharing stages with Butthole Surfers, Red Hot Chilli Peppers, The Ramones, and Cosmic Psychos. Pic: What are you listening to at the moment? Keish: I've been revisiting Are We Not Men, we are" Devo " lately, and our bass player Ray put me onto Dungen, from Switzerland, I just downloaded their 2017 album so. They are a psychedelic rock band , they sound good in the car so that's good man. What's on the radar for 2018? We are putting out a new album, and we want it to be something special, something that people really stop and go 'WOW!' as we've never done an album as a 4 piece before. It's well underway, the last few weeks have been jamming new ideas and growing the album really. We've been busy with gigs , so it's nice to be jamming for a different purpose other than getting ready for a show, it's been a lot of fun. Hard-ons are also returning for their 19th European tour... Yeah, I think that's about right, We are playing a huge festival "HELLFEST" in France with ahh, Judas Priest and Iron Maiden headlining I think...Joan Jett, Hellacopters, also...it should be fantastic. I haven't played any festivals for a long time so really looking forward to that. Europe is such a good time for us, the people are so accommodating, the promoters all look after us well. You know touring can be really hard if you haven't got good people helping you out so it's great they look after bands so well over there and the crowds are really cool. Fun times! Going back to the new album...what is the songwriting process for The Hard-Ons like? Well Blackie is very prolific in creating material, (yes he is, solo he put out a studio song a day for the entire 2016 year! Plus (Psychedelic punkers) Nunchukka Superfly, so he comes in with plenty of songs and ideas. Over a coffee, Blackie said to me we that need a new record as a 4 piece with you back in the band . So it's fresh for everyone in The Hard-Ons ya know...we have a formula for our sound, it will be some power pop, with punk n metal and melody in there as well. I've got some songs also so it's a new collaboration on an old formula, We won't stray to far, I remember "too far gone" kinda went over people's heads, we wanna keep our fans happy but also force 'em to take notice and be like 'WOW!; with the new material, take it to another level aye. It's a winning formula... Yeah mate ha ha I like it...hopefully it should keep us going for another 10-15 years. You're back in NZ and Raglan within a year of your last visit...it had been quite some years between previous visits... We just really enjoyed ourselves so much last time, the tour management and the Y.O.T club looked after us so well and the gigs were great with great bands Contenders & Illicit Wah-WahZ. The Y.O.T club was an absolute blast to play, a real loose party atmosphere, your'e very lucky there with such a great venue and owner. We met some great people and are amping to come back and deliver some new tracks for them and everyone who wants to get along for a piece of power pop/punk paradise!

1 Comment

A R T I C L E

Interview with Elephant Facelift with Ian Duggan Elephant Facelift are a new band in Hamilton featuring a couple of familiar faces. We interviewed Sam Brockelsby and Albert Bannister about their sound, aspirations and potential family rivalries! HUP: Albert has featured in a series of bands, including ‘Goth and the Pixie’, ‘Wink Wink Nudge Nudge’ and ‘Ancient Tapes’, while Sam fronted ‘Ancient Tapes’ through their existence. Does the sound of ‘Elephant Facelift’ feature commonalities with any of these bands, or are you something different again? (feel free to mention any influences here) Albert: Every other band in I’ve been a supporting musician playing other people’s songs. For a while now I’ve been itching to write my own songs and sing in a band. We’re both using Elephant Facelift as a chance to mess around with song ideas that haven’t fitted the style of other projects. My main influences are largely grunge, post-punk, and prog (The Mars Volta, Radiohead, Nirvana, and local heroes Mermaidens). I don’t have great upper vocal range so my favourite vocalist is Johnny Cash. Sam: No, it's quite different really, and for me that was kind of the whole point. After doing the shoegazing thing with Ancient Tapes, I was keen to try something else. I've always been into prog and space rock, and it has been really cool working those genres into the Elephant Facelift stuff. I'm also the only guitarist, and so my guitar playing has to do a lot more work than in previous bands. And best of all, I get to use my fuzz pedals as much as I want without infuriating the other guitar players. HUP: How many gigs have you played so far? Sam: Two since we formed in Feb. HUP: At the Graeme Jefferies gig, you were higher on the bill than Albert's dad, Matthew Bannister. Did this lead to any family tension? Albert: Haha no, my dad is not competitive so it was chill. HUP: What are your aspirations for the band? I understand Albert is heading overseas soon; is this the end already? Albert: I’m going to be back in July so it’s not permanent. We’re both just looking to play as much as we can while we’re both here. The duo format makes it really easy to practice and write new material. Sam: I think we're both keen to keep playing once Albert is back - play more shows and maybe get an EP or something out there. HUP: Who writes the songs? Sam: Both of us. HUP: What is behind your name, ‘Elephant Facelift’? Albert: One day I was watching Planet Earth and started thinking about what would happen if you injected elephants with botox. Visit the Elephant Facelift Facebook -> HERE <- A R T I C L E Enoch Interview By Andrew Carter I’m sitting down with three members of a Hamilton metal band called Enoch. Lorraine Brodie, John Brodie and Michael Germon rest patiently on a black leather couch. Michael is wearing a black leather jacket with dark blue jeans; John is repping a Metallica ‘Ride the Lightning’ shirt and black jeans, with his long hair draping over his face (full bogan); and Lorraine is dressed nicely with a long sleeved white top, black jeans and her hair tied back. I am in appropriate metal attire, full black, leather jacket and jeans, about to interview these three peculiar people. And here we go! HUP: Tell me about the band’s history. Who are your members and how did you meet? John: I met Lorraine years back. Lorraine: In 2011, and we were in a different band at the time. John: Yeah, we were in two different bands and we met through someone we knew and then I moved cities and joined Lorraine’s band (which dissolved), and then we started our own band which was Enoch. Lorraine: Then we decided to move from Christchurch to Hamilton where we found Michael, and then we found Ross. Michael: I got in contact with John and Lorraine through NZBands; they had an ad up, I applied, and it worked out. Then we jammed for a month or two, tried one other drummer and then got Ross in and that’s been the line-up ever since. HUP: How do you describe your music? What is your genre and what are your favourite bands? Lorraine: We’re probably like Alternative Metal and then have a kind of Nu Metal sound to some of our songs. Michael: I feel like Alternative Metal is what you say when you don’t know what you’re called. John: So we’ll say Alternative Metal, haha. Michael: When I joined the band Enoch’s sound was very Korn and Sepultura influenced. I enjoyed more Metalcore bands like As I Lay Dying and August Burns Red. Stuff like that. Got into Trivium and Parkway Drive and now I’m into Arch Enemy and Black Dahlia Murder. Probably the closest bands to the genre I listen to would be Mudvayne and Slipknot. John: My influences are Korn, Sepultura and Soulfly. Skindred as well, but also more mainstream metal bands. Pantera, Project 86 and P.O.D; stuff like that as well. Lorraine: I grew up liking bands that had female voices, or female solo artists. I really like Tattoo and I quite like In This Moment, but I also listen to some really heavy stuff like Impending Doom and Living Sacrifice. So really a wide range of stuff. HUP: Would you call yourselves a Hamilton band? John: I was born in Timaru but I moved around a bit and would say Hamilton is definitely my home now. Lorraine: I think the home of the band is between Hamilton and Auckland, ‘cos we’re half there, half here. I’m from South Africa but I consider New Zealand my home, because I moved [to New Zealand] when I was 13. Michael: I was born in Auckland, lived in Australia for 4 years, and have spent 10 years in Hamilton. Hamilton is definitely home. HUP: Who writes the songs? Is there one main writer or does the whole band write together? Michael: When I joined the band there were four songs written already, so I had no input at all, but then John and I worked as a writing team. I think I have a big influence on the melody and harmony of the song and John has a big influence on the groove and the rhythm of it, so it’s kind of two sides of the same coin and it works really well. Lorraine: Usually Michael and John will write something first and then Ross will come up with a cool drum rhythm for it, and then I write the vocals and lyrics at the very end, although we have some songs where the vocals were written first. HUP: Tell me about the new single. What’s it called and how will it be released? Lorraine: It’s called ‘Loner’ and it’s got a video that was done by Cloudfall Productions. John: We’re releasing it on the 27th of April on Bandcamp, iTunes and Spotify, and we’ll be releasing a video on YouTube and Facebook. It’s the first single on our upcoming EP, which will be released around August some time. Mordecai Records recorded the song. HUP: You guys performed at Festival One this year. Can you tell HUP about that experience?

Lorraine: Well first, when we arrived there, I couldn’t believe how well we were treated! They had cars for us and they packed all our gear and drove us around. There was this musician’s lounge that fed us for free. It was amazing. John: It was pretty sick. We played with some really good bands; Vanguard, Chasing South and Lead Us Forth. It was really good. Really good crowd response and they want us back next year. HUP: What’s your opinion of the New Zealand metal scene? Michael: I actually think in general it’s really good. All the band’s we’ve played with are real supportive. What hate there is is just keyboard warriors. The people who are actually out there really doing things are united really. I think the only problem is people not coming to gigs, hahaha. But I think it’s growing. Lorraine: I think for such a small place as New Zealand there is so much creativity in it. There are all sorts of genres. We are so blessed with so many different opportunities for events and gigs going on every single weekend that we’re spoiled for choice. It’s really good. HUP: Your band has Christian members. Do you identify as a ‘Christian Metal’ band, and if so how do you feel in a secular scene? Lorraine: I think we’re a metal band with Christian members in it, and because of our beliefs that will bleed through into our music that we put out. Though we have some Christian messages in our music the music is still for everyone. Mostly we play with non-Christian metal bands and we have lots of friends who aren’t Christians, and even Satanists, and we get along so well despite that. Initially, when we appeared on the scene, we had a bit of back-lash. But to be fair people didn’t know what to expect, and once they got to know us we became friends. Michael: We’re a band with Christians in it but I wouldn’t label us a Christian band. We’re just a band that plays with other bands. There’s been a bit of back-lash about Christianity but I wouldn’t say there’s been any more than for being Nu Metal, or being female fronted, or just not being Death Metal. The things people normally hate on, people will hate on, but I think in general people respect us for what we believe. HUP: If there was one thing you could tell the readers about being in a band what would it be? Michael: You get out what you put in. There are lots of people who would love to be in a band but are you willing to put the time and money into it? Is it rewarding? Of course. But you get out what you put in. Lorraine: Don’t be afraid to haul your gear through icy rain to get on a bus to get where you need to be, because we’ve all been there and you need to go through that stuff to get to the good parts and it’s so much more rewarding when you do. John: If you wanna be in a band, be in a band, and put everything in it. And if you’re a bassist change your strings, haha. Enoch’s single ‘Loner’ will be released on the 27th of April. A Q&A with Graeme Jefferies By Phil Grey, The Hum 106.7 Coming up on 26 April, Graeme Jefferies plays an evening of songs from his back catalogue, from his bands The Cakekitchen, This Kind of Punishment and Nocturnal Projections. The Hum 106.7’s Phil Grey caught up with Graeme and talked about the history of his bands, former Hamilton shows, what we should look forward to on the tour, and much, much, more... Phil: Graeme – growing up in Stratford, what was the first music that you recall having a profound influence on you, and how did that inform your early musical experiments? Graeme: It made one kind of dependent on local releases as imported records weren’t around then. My brother and I were keen record listeners and buyers and pestered our mother for money to buy records from a very early age. Stuff like David Bowie, Badfinger, Mott the Hoople, Cockney Rebel, The Velvet Underground were fairly typical examples of what floated the boat in those times. But also a lot of individual songs as 45’s too. We liked buying singles at first it as was easier to siphon the money for them because they were cheaper. With older brother Peter, you formed Nocturnal Projections in 1981, releasing material at first on cassette, then vinyl. The band has been described as an antipodean Joy Division. Is that a fair comparison? I suppose Joy Division is a comparison that I can understand because there were some elements of our stuff that were similar and we really liked Joy Division. But we had already written over 50 songs before we even heard Joy Division. Some of Peter’s vocals made the comparison easier to make. But there were also songs that sounded nothing like Joy Division. Musically we used a lot more different chords than Barney managed. If you look at how he played in Joy Division it was pretty much moveable E bar chord up and down the fret board most of the time. The Nocturnal Projections had a larger chord vocabulary and also played a lot faster than Joy Division. But it’s a fair enough comparison for some songs. The Another Year EP has some similar things to Joy Division. Phil: Following Nocturnal Projections you and Peter formed This Kind of Punishment, who gained greater exposure through releases on Xpressway and Flying Nun. The second LP A Beard Of Bees is now recognised as an NZ classic. It has elements of sparse instrumental work, experimental noise, and a clear Velvet Underground influence. Who in the band exerted the strongest influence on the sound? Graeme: That’s a hard one to answer in a meat and potatoes fashion because it really varied from song to song. By the time we got to TKP we had written maybe 100 songs together where I had written the musical skeletons and Peter had written the lyrics to accompany the completed music. I had also worked out a couple of hundred other songs that I liked that other people had written that we played together for fun growing up, with Peter playing along on drums and me playing electric guitar. Those were our specialized fields. I was more specialised in writing music and arranging songs and Peter was more specialized in writing words to completed pieces of music. So with TKP each one of us bought those skills to the table. Peter had no idea how to write music but had good ideas for spacing it. If anything (although the cut and dry answer I presume you want doesn’t always apply) I was still more responsible for the arrangement of the music and the getting it from an idea to a concrete music bed that could then have lyrics added. The words were always added after the music was completed. So I suppose I exerted a very strong influence on how to put the music into a way where it could have words added to it. Peter exercised the strongest influence lyrically. But we swapped things over and tried lots of different things to try and write different types of songs. TKP was deliberately undoing the style we had used as a writing team by analysing what we didn’t do and trying to do that rather than just writing songs without thinking about what sort of song we wanted to write. It was a very conscious effort to bake a different sort of cake. Phil: Were there any other musical elements left on the cutting room floor [so to speak], that you would have liked to be more prominent? Graeme: Most of the ideas that we worked on together we ended up using. At least for the first initial run of from the first album to the end of A Beard of Bees. Those two albums were written one after the other with no real gap and we didn’t waste a lot of ideas. Most stuff we finished and or resolved to our satisfaction. When we tried to put a live band together with Chris Matthews we had a lot more wastage and songs that somehow didn’t work so well or we got sick of and left behind. As a band it didn’t really work trying to write together and most of the stuff that we started with the Chris Matthews/ Michael Harrison line up didn’t get used. TKP was really a music writing and recording project more than it was a live band. The live thing was only a dozen or so gigs over a short period of time, but as a writing thing it was a straight year and a half of nonstop writing and then recording before we ever even thought about playing a gig or trying to recreate any of the songs live. Phil: How were the dynamics with fellow band members? Graeme: Um, everyone got on fairly well. We all had similar tastes and were all fairly introverted and socially awkward. There were three incantations of the group initially. The first was a recording unit; the second two were live band line ups that operated for a fairly short time in order to play music in pubs to kiwis drinking pints. Running through the people in it…….. Johnny Pierce had been managing The Nocturnal Projections and was a lovely guy. He had the best people skills. Everyone really liked him. Gordon Rutherford was the drummer from the Nocturnal Projections and in the first incantation of TKP was the recording engineer for the first couple of albums. Peter and I had grown up together and been working on bands for years from High School on. Michael Harrison was a painter who was moonlighting as a musician. He was a nice guy. The first live line up was with Peter, myself, Michael and Chris. When Michael left, Johnny replaced him. Peter had mentored Chris Matthews quite a lot when they first met. Chris was in this funny little pop band called The Prime Movers that played a show with The Nocturnal Projections at the Rumba Bar early in 1982. Chris told Peter after we played a show with them that he hated his band but really loved our band. He eventually persuaded Peter to ask everyone in the Nocturnal Projections group flat to let him stay on our couch for free because he had nowhere to go. So we let him stay there for free. He didn’t really have any money at the time. We felt sorry for him because he had nowhere to go. They became pretty good friends and would spend hours talking together. So you had that dynamic between those two added to the inter-workings of how the rest of TKP operated. I never really knew Chris very well. Still don’t really. He didn’t write very much of the material in TKP and songs of his like The Sleepwalker were written outside of TKP when he was in a band called Children’s Hour. Strangely enough they didn’t want to use the song because they thought it was too wimpy, but Peter and I really liked it and helped Chris get it out by recording it as a TKP song with Gordon Rutherford. Gordon has never really been acknowledged as a member of TKP very much, but he worked on every song we did for the first couple of albums and did all of the engineering. It’s funny how people perceive bands in a way. TKP was a recording project more than a band and Gordon was definitely a member of it. Phil: TKP, like Nocturnal Projections [and arguably the Cakekitchen later], music could best be described as sombre. Is this something that band members cultivated, or did it truly reflect something from within? [Jefferies has alluded to this - “1985 and 1986 were pretty bad years (for me) and I think that’s reflected on the record” [Audioculture.co.nz]] Graeme: Oh, I hate people trying to describe our music because to me each song is different from the previous one and they are all meant to convey different feelings and emotions. I guess some of them were a bit sombre but everyone in those days was very young and intense. So I guess that that’s going to come through in the music. Particularly if you analyse the lyrics and say that that is what the song is meant to be about. But the music was always written first as a blank canvas for the lyrics and had an emotional essence that usually had more to do with the joy and beauty of the world or the share pleasure of sound travelling through pockets of air than being sombre. Once the words are put in place people tend to forget that the music had a deliberate feeling and meaning of its own, in an emotional sense, and I usually saw these invisible type meanings as being uplifting and full of the vigour of life and the mystery and beauty of life more than being negative, sad or sombre. The Audioculture piece you referenced is written by somebody who doesn’t really like The Cakekitchen much, or know very much firsthand about what it did or why it did it, and was made up by cobbling bits out of our dot com site and without any direct interview or question asking to see if he had it right. It also hasn’t been updated to include the last two full length releases and misses the point on a lot of things. I wouldn’t pay much credence to what it says. It’s funny that even the compliments are half arsed in a way. He thinks we made one classic album in 1991, which kind of means that the all the albums since then have presumably failed because none of them to him are considered classic. But he never even really says why the one he thinks is classic is good and why the others aren’t. In a way it’s like saying we haven’t made a good record in 25 years. If I did a similar thing and reviewed every article he had written for 25 years and said that one of them was a classic piece of writing but left a pregnant pause over the other quarter of a centuries work he did, I imagine he wouldn’t be that pleased about it either. The lay out and video inclusion of the Audioculture piece is good though. I suppose, all in all, it’s a presentable enough effort to touch on some of what we did, but I wouldn’t use that as a reference to the Cakekitchen if I were you, because it’s fairly obvious that it’s written by somebody who doesn’t really like or understand what we were trying to do. The press and public representation thing is a funny beast and just something that I suppose we all have to put up with. He obviously has his favourites and The Cakekitchen isn’t one of them. Never mind. There are better pieces of the group in other locations. Phil: The tour coincides with the rerelease of Nocturnal Projections material. Any nerves about this material being heard by a new audience? Graeme: Oh, it was me that put all of the production master material together for the Nocturnal Projections reissues. So in my opinion they are really good. The album of unreleased material in particular should be of interest to anyone who liked what we did. I went to a real lot of trouble to go the extra mile on the quality for that one and the song selection is really strong. The studio recordings that were released during the bands life time make up a really good complete ten song album that runs well together. I still really like this material and the mastering quality of the new version of this material is very good and a joy to hear after all this time. There’s still enough material in the archives for maybe another volume of songs to be added at a later date. The Nocturnal Projections had over 100 original songs and most of them were never released for one reason or another. So it’s a welcome opportunity to shed a bit more light on a few very well kept secrets. The only thing that’s made me cringe with The Nocturnals was the Worldview seven inch that was released while I lived abroad and culled from our first cassette release. If I had been asked about it before hand I never would have agreed to release it. You can’t hear the snare drum on any of the songs on it. So all the drum parts are totally inaccurate to what Gordon Rutherford played as drum parts. I thought it was a bootleg and bought one for ten bucks when I saw it thinking it was a bootleg. But apparently Peter had done a deal with a guy who wanted to bring it out and just not bothered to ask anyone else who played on it if they wanted to do this. Phil: How did the collaboration with Alastair Galbraith [of The Rip, Plagal Grind] on 1989s Timebomb 7 inch come about? Was there any further material recorded? Graeme: After TKP had broken up for a year and then Peter and I had decided to give it another shot and resurrected it in Dunedin in 1986, one of the projects we did there was to record the second Rip record on my four track in the house we were renting. It was mostly an acoustic record of Alastair plying most of it but Robbie Muir did play on it too. After about 4 months I left Dunedin and set up my studio in Christchurch, when Alastair was passing through Christchurch on his way to emigrating to Melbourne. He happened to drop in and I recorded the songs that eventually became the single as a favour and a historic last stand on native soil. He was meant to be leaving for good but after a few months he decided he didn’t like Melbourne and came back. I was given carte blanche to whatever I wanted to the songs he left and when I felt I had gotten it right I sent it on to Alastair in Melbourne and he really liked it. For the next couple of years I would occasionally send him something to work on and he would post it back. He played a marvellous violin part on the Cakekitchen song, World of Sand. He was always really enthusiastic and easy to do stuff with. Out of anyone that I’ve helped to do a record he’s one of the few that’s ever actually paid it back by giving something back in a musical way. It worked pretty well doing stuff with him. Phil: The Cakekitchen is a band with a rotating cast of members. Formed in 1988 a highpoint was the attention [mainly through NZ student radio stations] of releases such as Messages For The Cakekitchen and the band’s breakthrough 1989 EP that contained classic Cakekitchen tracks Dave The Pimp, Witness To Your Secrets and Airships. Looking back nearly 30 years later, what’s your recollection of this period of activity? Graeme: The original Cakekitchen was a two piece band with myself and drummer Robert Key that added Rachael King as a bass player after a few two-piece shows. As a unit we lasted a couple of years and eventually went our separate ways. Messages For the Cakekitchen was an album of material I started writing when TKP broke up for the first time in 1985. It’s much more like a TKP record than anything else but without Peter’s vocals. It was completely finished off as a record before the band line up of the Cakekitchen ever existed. It wasn’t as the Audioculture site states a thing that contained all the seeds of the band to be. It was a separate thing on its own, containing a collection of material I wrote with no intention of making a record at the time, but just to keep doing what I was doing after TKP broke up. The Cakekitchen EP was culled from the groups first year of playing together. Airships wasn’t on it but a two-piece version was on the Xpressway Pile-Up. Other material from that first year was added to EP material to make up the first Cakekitchen album released by Homestead in the USA. The second Homestead album, World of Sand, contains most of the other band type songs from the second year of the original bands activities, and the best examples of what we were doing live at the end of our time together. Both the Homestead albums also have a few acoustic songs or recorded on a four-track; songs that Robert and Rachael didn’t play on that I wanted to include to mix up the style of the album a bit more. The four-track Cakekitchen songs on the Homestead albums are closer to TKP type songs in style and recording than what the live band was like. Looking back thirty years my recollection of those times is that we were fairly solid as a band. We rehearsed two or three times a week and had a lot of fun and satisfaction doing what we did. It was all pretty organized, fun to do, and worked pretty well without anyone having to pull teeth to get a good result. I enjoyed working with Robert and Rachael and we had a lot of fun doing what we did together. Phil: The Cakekitchen played at least one memorable gig in Hamilton. Do you recall playing here, and did your earlier bands ever play here? Graeme: Yeah, I remember the last time I played in Hamilton. It was with the 1994 two-piece line-up with Jean-Yves Douet. It was his first show in New Zealand. I remember that I forgot to take my jersey off before we started and almost had steam coming out of my ears by the time we’d finished. I like to go straight from one song to the next and build up a tension in the performance by not letting it get luke-warm with too much blah-blah-blahing inbetween. So I didn’t want to stop and take my jersey off. It was a fairly good show and after that tour I did with Jean-Yves it took 11 years before I made it back to New Zealand to do another show, because the band ended up being based in Germany after that and concentrated on playing Europe and the USA instead of playing down-under. We never had enough financial resources to swing the flights for coming back home and in fact if a guy called Paul Toohey from the Arts Council hadn’t helped us apply for a grant to soften Jean-Yves air fare expense we wouldn’t have been able to do the Hamilton or the New Zealand tour at all. I’d played in Hamilton with Robert and Rachael a couple of times before that. Once on an Orientation Package Tour in 1990 and once in a small club the year before as a test gig for Rachael’s first show with the band in April of 1989. TKP and the Nocturnal Projections never played in Hamilton. Phil: From a local perspective, the band largely petered out around 1990. In reality, you had headed offshore, and over several years built a pretty solid following. Where were you based, and where did The Cakekitchen enjoy the strongest following? Graeme: I left New Zealand in August of 1990 and based the band in London for three years, France for a year, Holland for about 3 months and Germany for about 12 years. Various incantations of the group did a total of 8 European Tours, 3 American ones and loads of shows on the continent on a one off basis. Since I financed it all on a shoe string there was never the money to come back to New Zealand and it was better to concentrate on the Northern Hemisphere which is a massively bigger market sales and profile wise. We didn’t have any business dealings in New Zealand once I left, so I suppose that it did look like me disappeared but in fact we had a much bigger profile internationally than we had had before I left and did far better than we ever could have done by staying in New Zealand. It wasn’t so much disappeared as surfaced on the other side of the world. It would have been nice to have been able to retain a kiwi market too but if you can only afford one set of operating costs then the bigger worldwide market was the obvious one to go for because it was on a much larger scale and operated in a much more lucrative way than the old 1990s Flying Nun scene that we were part of. Phil: The Cakekitchen music ranges from the power of Airships to many beautiful [but less known] tracks from later albums. What’s your preferred sound now? Graeme: That’s a tough question because my preferred sound changes a lot from song to song. I try and use a broad palette of colours to texture the music with and it really varies from song to song. I also play a lot of instruments and this really changes the texture from song to song to. Trying to answer the question in the way I imagine you intended it I guess I use distortion and the brizzle brazzle of guitar distortion pedals less than when I was continually playing electric guitar in a live band situation. But I still use it in the shows. Just shorter bursts for maximum effect. I like the contrast of not using it and then suddenly adding it in. I tend to use more pastel shades than harsh metal ones these days for the recordings but that can change at the drop of a hat depending on the song and what you want to convey with it. Since by and large I spend much more time recording than I do playing live I tend to not use that much the usual band type artillery of sounds that you hear when you watch people playing rock music in bars. The idea with a show is to vary the sort of sounds and the sort of songs you do as much as possible during the course of your set. To try and push the boundaries of what can be done on stage in performance as much as possible in a show and to emotionally deliver as varied a set of feelings as can be portrayed in a live performance setting. Phil: What instrumentation can we expect on your upcoming mini tour? Graeme: Live for the upcoming shows I will be using electric guitars and electric pianos and vocals, drawing on a selection of material from all of the musical projects I have been in. Playing by myself has the advantage of being able to vary the performances radically from gig to gig and town to town. You can change to performance as you go along and no-one will know if the next song you play is one that is on the set list or one that’s just come off the top of your head. I will be paying a lot of the recently re-released This Kind of Punishment songs in the set as a way to salute the recently made available again material and to offer an alternative version of the songs to the one the Peter and Chris presented in Auckland last year at the Golden Dawn show they did. Some friends told me that they murdered a few of them so I figure it can’t hurt to do them properly again in a live setting for the small amount of people still interested in hearing the material in a one on one type way. Phil: Your autobiography ‘Time Flowing Backwards’ is about to be released. Can we expect any Mick & Keith type revelations? How’s that relationship? Graeme: No the book doesn’t offer any Mick and Keith type granny knickers mithering sessions. The purpose of it was to tell the story of my life since leaving New Zealand and to detail in an honest way how I survived and prospered in the International Music Scene by living outside of New Zealand for 17 years. It talks about things like recording and playing in Russia, living and operating in London, living illegally in France for a year. Living in Holland and working for a large music distributor in Germany. I worked on and off for Rough Trade Germany for 7 years. I had hardly any press in New Zealand while I was living abroad because I didn’t have any ties with the old-boys network here. So these stories and wild adventures are new for kiwi readers. The book also talks about a lot of non musical things and how I view life and some of the secrets about it that living it has revealed to me. Without getting too cosmic. It was originally 480 pages and has been cropped down and edited to a little over 300. The editing process has been going on since the original draft was finished in October of 2014 and I have updated it as time has rolled along. We are now down to the final proof reading and have hashed over the re-written pieces and the deleted parts to where both myself and the guy who’s publishing it are fairly chipper with it. It will be interesting to have it out there in the market place but it’s slightly disconcerting to know that people will have access to so many of my personal secrets without the benefit of me telling them first hand in a conversational setting about it. It’s a hell of a good read in a way and is unlike anybody else’s take on what it takes to survive in the music industry with no manager, no publicist and only using independent tour organisers who work on a 30% of the gross profit basis to organize your tours. It doesn’t dwell on the bad things or the grumbles but tends to focus on the good things and the funny stories. Peter and I mutually agreed to stop writing together in 1986. After 6 years of writing and playing together all the time we had somehow become like two lions in the same jungle and we needed our own space to grow as artists and also as people. So we aren’t like Mick and Keef who got stuck together for years and years and years just to keep the money coming in and the show rolling along. Phil: Around 1989 my old mate Grant McDougall sat down and interviewed you for Critic. You described yourself as ‘shy and highly strung’.

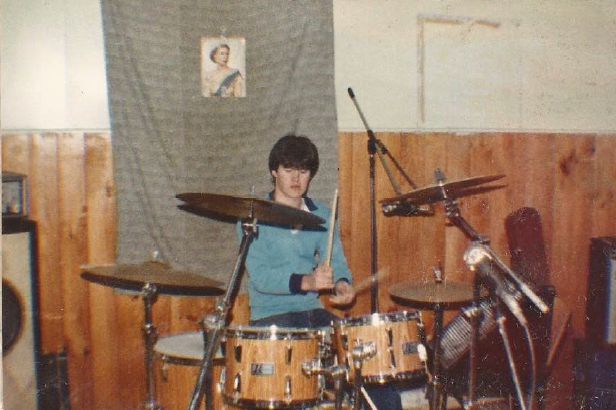

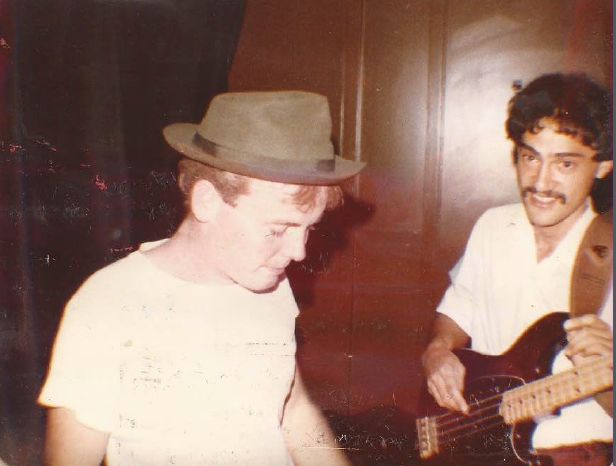

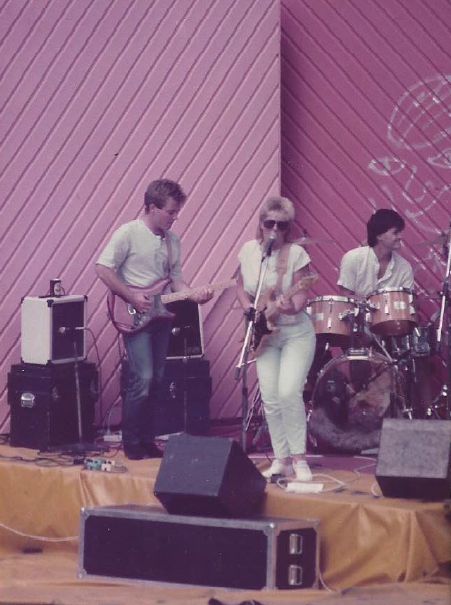

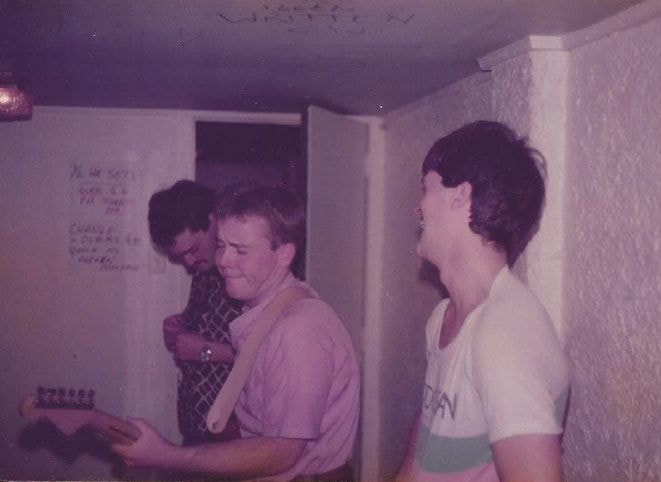

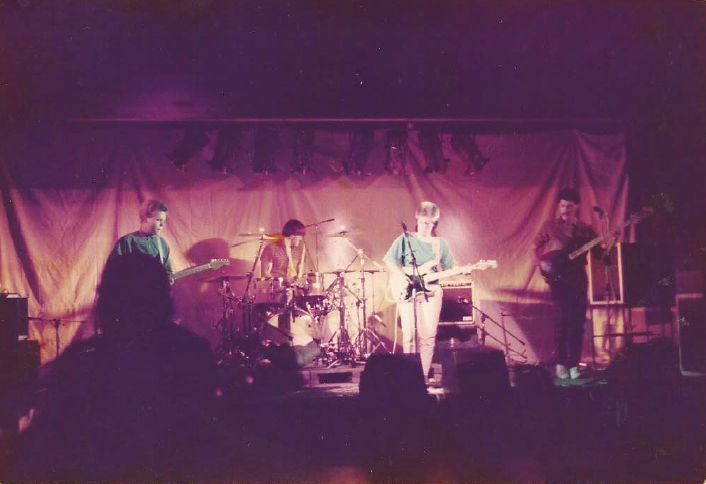

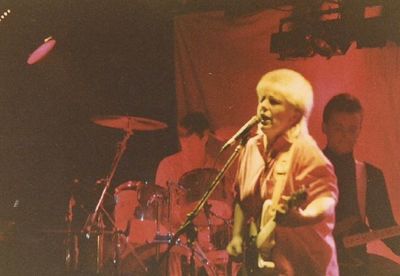

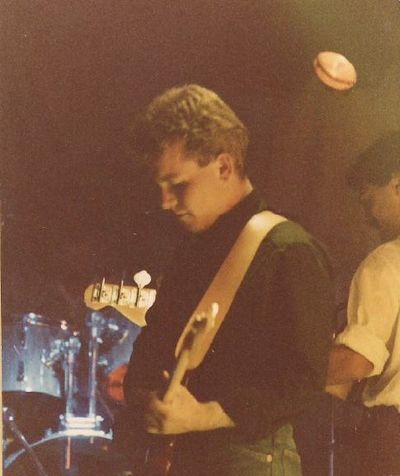

Graeme: Ah, Grant McDougall. He was a friendly guy. I remember talking to him in Dunedin before we played at the Empire there. I think I’m still probably shy and highly strung. Perhaps my skin has gotten a little harder over the years but I enjoy feeling things and am shy and highly strung because that is how I am or how living in the world makes me. I like being this way and am this way by choice. Phil: As late as 2005 you were talking about a preference for solitude. This seems at odds with a career in performance. Care to comment? Graeme: Your feelings are all you have and should be treasured. They are the difference between you and the rubbish tin across the road. It’s a fairly hard world out there but I would rather feel it than not feel it and I am happy in my own skin. I don’t see this as a contrast to being a performer or enjoying solitude. The performance is only a small part of the day and I like performing and being on stage but I also enjoy my own company and the solitude that you need to court to write the material that you perform. I chose to be by myself a lot of the time by choice. I like being this way. It doesn’t seem a contradiction to me all and I think a lot of performers and artists are actually like this. Phil: What’s life like for Graeme Jefferies now? Graeme: I live in Wellington at present. The studio I shipped back after financing with my song writing profits from the years of success living abroad fits onto pallets and I ship it to whatever country I want to live in so that I can keep making records and writing songs. I earn my living by other means and only play live when I decide that it’s a good idea to. I usually spend most of my music time writing and recording and I still release new records and CDs internationally when I want to. It’s the logical conclusion to many years survival as an artist and songwriter. Like I’ve always done; I still write and record exactly what I want (minus the limitations of my lack of talent or ability to do so) and keep staring my little creative boat down the river of song. I have a small but dedicated fan base that support what I do and keep me a float and stop me from getting big headed. For the time being I am quite happy to be in Wellington but if for whatever reason I decide that I want to go somewhere else I have the resources to do so and the pallets to pack it all up on again and ship it to the next port of call. It’s the perfect artistic existence in a way because it’s self funded and keeps itself going without outside intervention or need for approval. I can still do exactly what I want. Phil: We’re really looking forward to your gig [Nivara Lounge, Thurs 26 April]. What’s in the setlist? Any particular highlights for you? Graeme: Thanks, I’m really looking forward to playing it. I hardly play in New Zealand very much these days and even less in the top of the North Island. I haven’t quite decided what’s on the set list yet and I will just decide on the day itself. I’ve been rehearsing a lot of different material from all aspects of the music that I am known for. Nearly every song I have ever recorded is possible to still play. But I will just see what I actually feel like on the night itself. I’ve got some pretty big blisters on the end of my fingers already. So anything is possible in a way. I spent the last couple of weekends screen printing a special back drop for the shows and have gone to a lot of trouble to make the night something really special. I also did a limited run of about 20 TKP tee shirts made especially to sell at the shows. It should be a lot of fun. A R T I C L E A Retrospective Interview with ‘The Wetbacks’ Ian Duggan, with Jeff Sinnott, Dianne Archer, Chris Corby and Pateriki Hura The Wetbacks were a popular alternative Hamilton band from the mid-1980s. The band released a vinyl EP in 1985 called ‘Out of the Swamp’, and later had a song called ‘Don't get Caught’ included on the 1986 National Student Radio compilation ‘Weird Culture, Weird Custom’. But who were The Wetbacks? Between 1982 and 1986, The Wetbacks carved a small, humble niche in the New Zealand music scene. Based in Hamilton, at the time not really the epicentre of anything much except large tracts of peat swamp, cow shit and corny blues covers bands, The Wetbacks was born out of as much frustration as they eventually self-combusted in. Born of myriad musical roots, from folk, reggae, jazz, punk and good old-fashioned rock & roll, they gradually formed a unique sound that ran both alongside and counter to the post-punk, pre-grunge era of the early 1980s. Much has been written of the Flying Nun/Dunedin sound in New Zealand during this time; one that glorified the raw song-writing, low-fi, angst ridden energy of bands like The Enemy, The Gordons, The Clean and The Chills. This label probably did more to establish New Zealand’s music credibility internationally than any other label in our musical history. It is a label that has stood the test of time and now, nearly 40 years later, still rings true. Yet there was a small spark of a cleaner, dare we say, more produced sound happening further north. Not the sterile, commercial radio influenced pop emanating from studios in downtown Auckland. But something that hybridised the social commentary of the southern sound with the musical sensibilities of the north. Yet the greatest pity of all is that this small, yet significant force, quietly slipped away pretty much before it was noticed. We need mention no names, but ‘80s New Zealand music was riddled with bands rising from wellsprings such as Sacred Heart College in Auckland, the pubs, houses and marae of the South Side, the clubs of the Shore, and the studios of several successful musicians of the 1970s with enough nouse to invest in facilities and technology that enabled another generation to scratch their itch. New Zealand music was generally divided by latitude at that time. In the south it was all angst-ridden, teen spirit, resulting from new-found freedom; booze, sex, drugs and a sense that “fuck it, we can play anything, even if we can’t pay anything”. The veritable three-chord bash, played with enough chutzpah that could pass as marketable (or un-marketable) music. In the North it was whatever would get you in front of TV show Radio with Pictures, commercial radio or on the infamous ‘Do Da Coruba’ Tour. What had proved fertile ground for the English post punk/new wave sound of the likes of XTC, Shriekback and The Jam, made sense to a bunch of musos in Hamilton. Dianne Archer, a Waihi local, guitarist extraordinaire, and as yet undiscovered vocalist of considerable talent, met up with Jeff Sinnott, a young impressionable drummer, fresh out of high school in Hamilton and gagging for an outlet for his musical excesses. Cambridge guitarist Chris Corby brought his layered, textural nuances, deft song-writing and penchant for obscure lyrics. The line-up was complete with the addition of Pateriki Hura, who joined initially on guitar and then replaced original bass player Paul ‘Scooter’ Donnelly. Hamilton Underground Press caught up with Jeff Sinnott, Dianne Archer, Chris Corby and Pat Hura to explore the memories of a band that one Australian music critic, 3RRR’s Richard Wilde [a.k.a. Richard Wilkins], described as ‘one the greatest bands that never was’. HUP: The Wetbacks, how did you come together? Jeff: The band kind of evolved when Di and I met in the early 1980s. Dianne: I was looking to get a band together when I met Jeff. Jeff: I think I may still have been at high school. Anyway, we got together with Paul ‘Scooter’ Donnelly from Thames who had a fascination with the whole UK punk thing. Di and Scoot had previously met at a punk gig near Hamilton so it was easy to get things going. Dianne had come from Waihi and was a great blues guitarist that had discovered punk. I remember meeting this crazy, purple haired lady, pulling up on a Suzuki road bike with a guitar strapped to her back and laying us out with her incredible playing, as well as a voice that could cut steel. So, after a few jams we started a kind of thrash three-piece thing in late ’82 called ‘Rhythm and Skins’. I think we did one gig, realised we weren't that good so got on with practicing, wrote a bunch of songs, tried out a few other players, drank way too much Whisky, busted out a few urban commentary riffs like ‘Life of the Lifeless’ and ‘Buy Me’, and worked on our versions of covers like XTC's ‘Radios in Motion’ and the La De Da's ‘Land of 1000 Dances’ - the latter of which never failed to fill the dance floor at the Hillcrest on Bursary night. Incidentally, ‘Lifeless’ and ‘Buy Me’ were two songs we never got to record but by hell they were fun to play live. Jeff: Scoot and I flatted together in a cold, damp house in Wellington St and practiced all winter of 1983. We developed a kind of galloping, punchy, rhythm section sound that we felt just needed a decent guitarist. Enter one Pateriki Hura, who had answered an ad in the paper for a guitarist. Well one jam with us raucus lot by a Taumaranui boy brought up on a diet of Van Morrison and Bob Dylan had him hightailing it back to Waikato Uni as fast as his treadly [bike] could take him. Di came back in the spring of ’83, which we celebrated by throwing a huge party that pretty much got us kicked out of our house. But as we had practiced and sounded cohesive of sorts she decided to re-join and start to formulate a plan for global domination. As Scoot used to say, lead bass, lead drums, lead guitar - subtle we were not, but I believe we had a pretty unique sound. Dianne: I left the country for a short time and when I returned Chris Corby had joined the boys, and I rejoined and we became 'The Wetbacks'. Jeff: We felt that while playing as a 3-piece, guitar, bass and drums, worked for The Jam, it didn’t quite work for us, so I gave an old mate a call. Chris Corby and I had met a few years before when we were at Intermediate school. His older sister Liz had been at school with my sister Anne and she recommended we get in touch, so he brought his unique guitar sound and sensibility to Dianne’s impeccable rhythm and The Wetbacks were born. We played our first gig as The Wetbacks at a friend’s 21st in Tirau and literally brought the house down. From memory there was an all-in brawl between the local metallers and these blow-in punks from up the road. There were bottles and people flying everywhere and we were lucky to get out with ourselves and our gear. This was the gig that our eventual sound tech, manager and old school buddy Kevin Oliver joined us. Chris: [Kevin was] our sound guy and truck driver and all-round top bloke. Supporter number 1 - every band needs one! We both joined the band together at the same time as I recall, [being] school friends and flatting together at the time. Kevin went on post-Wetbacks to mixing bands like Herbs and Flight X7. Like us he was very green and wide eyed, but were all on a quest and it was brilliant fun. Jeff: He had a pretty good ear, even if he was a hopeless Joy Division addict. We forgave him because he looked like he knew what he was doing on the desk. Chris’ brother Pete, a stunning drummer in his own right, also joined us on this escapade as a roadie, lighting tech, barman, doorman and bouncer. From there we moved on to the Coromandel, and Raglan, and strangely enough started to appeal to the surf-punk scene that was emerging at the time. It seemed we were seen as a local imitation of the Butthole Surfers. Gigs like the Rob Roy in Waihi, the Whangamata Hotel and Waihi Beach pub were favourite places to play where we could work on songs, learn how to play together and work on our show. Eventually we started to get gigs in town [i.e., Hamilton], got ripped off at places like the Lady H, and wrote a few new songs. [Our songs] ‘Fighting for the Right’ and ‘Watching the Skyline Grow’ had their genesis at that time. Scoot left in late 1983 to go on his OE to his ideological hometown of London, where I believe he still is today. That led to us putting an ad for a bass player in the trusty paper and who should answer but our once-time guitarist Pat Hura; this time on bass and this time to stay. Pat: The Wetbacks were hard left of everything that was happening in the Hamilton music scene in 1983. I saw them at The Hillcrest Tavern and was simply blown away with their raw energy and their fresh look. Their short spikey hair and bright clothes were the opposite of what mostly was on offer. The town needed something like this. I had meet Jeff and Paul earlier that year when Di had split from the band. We had almost no music in common but shared a drive (or a fanaticism) to play. I liked them a lot, but I was not the right guitar player for them. Funny, it was not easy getting an audition when Paul left The Wetbacks some time later. I answered the bassist wanted ad in the local paper and was turned away by Dianne a number of times. Thankfully Jeff joined the dots I think and I auditioned on borrowed equipment and got in. Dianne: Paul left and Pat joined us. This was an exciting time, as Chris, Pat and myself were all writing songs. We used to have band practice in an old cowshed at Chris's parents farm. It was freezing in winter, but we were young and keen and it didn't bother us much. Chris: Yes, it was bloody cold but it didn’t matter of course. We were in a band and we were committed. My Dad had handed over the old woolshed to my brother Pete and I and we created a little stage inside for rehearsing our respective bands. I do remember we had to run the power cord across to the cowshed about 20 meters away for power and cows sometimes would shit all over that lead, and it was a dirty chore rolling it back at the end of rehearsals! Did I mention commitment! Dianne: Our aim was to have about thirty original songs before we started gigging. We were adamant we weren't going to take the easy route and play covers, which so many bands were doing at the time. We were young and naïve and in hindsight should have had management... Jeff: We more-or-less locked in straight away. Pat was a huge folk fan so he offered quite a different dynamic to Scoots from the hip punk style, and The Wetbacks evolved in a slightly more melodic direction. Still very lively, still full of angst, [and] still raging about the injustices we saw on a daily basis both in New Zealand and overseas; themes that pervaded through our lyrics for the entire time we played together. We saw ourselves as a mouth piece for social justice and were heavily influenced by the likes of Billy Bragg, John Cooper-Clarke, Marley, Dylan as well as the more subtle pens of Joan Armatrading, Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell. Songs such as ‘Poison Rain’, ‘Entertainment’ and ‘Silent Man’ emerged during this period, from mid ‘83-early ‘84. HUP: So was it ‘Wetbacks’, or ‘The Wetbacks’? How did you name yourselves? Jeff: ‘The Wetbacks’. Probably not the most PC name these days, but it seemed to work back in the day. From memory the name came from a conversation around the politicisation of the boat people arriving on the shores of northern Australia and made us think that in general nearly all of us are boat people in a sense. Whether we arrived on camels, ocean going waka or tin planes, we are a nomadic species that has distributed itself around the planet. So, the notion of ‘illegal’ immigration is a little strange when we’ve been doing it for millennia. But we thought ‘The Boat People’ was a little too provocative, and that we may get confused with the Village People! The conversation turned to so called illegal immigration in general and I recalled a book I read about Wetbacks, Mexicans that crossed the Rio Grande into the USA raising the ire of the political elite, and used as a wedge to encourage paranoia and a badly misplaced sense of nationalism. So, we decided on the Wetbacks as a great name. It was short, catchy and had a political ring to those that bothered to think about it. HUP: What were your impressions of the Hamilton scene during your time together? Where did you play, and who with? Chris: Hamilton at the time was of course a very strong Uni town and I recall many gigs at the Hillcrest Hotel in the band room, with strong student support, and many support gigs for touring bands. Jeff: The Hamilton music scene was filled with blues and covers bands that, while played by some extremely competent musicians - many of whom were our mates that we jammed with - weren’t really to our taste. We decided that if we were to make an impact we had to write our own stuff and perform it to people who understood it – and given the appetite for Top 40 pub rock in The Tron, the Uni was the obvious target. Chris: There was quite an underground Punk and Ska scene in the early ‘80s and The Wetbacks had a core group of people following us for a time who rode mopeds and wore Doc Martins and turned up at many gigs. I recall that core once riding their mopeds all the way across to Waihi Beach and turning up at one of our many gigs there. The frustrating thing for us was perhaps our isolation from the main Kiwi music scene in Auckland, and I know we tried to push in up there and get support but never managed to get it going unfortunately. There wasn’t any internet of course and making connections was by phone and meeting someone at a pub for a chat. It was all very D.I.Y. We put on our own gigs and hauled around our own P.A. with our little lighting rig in our own truck. We stayed in tents and friends couches and shitty motels. Brilliant! Dianne: We mostly played at the Hillcrest tavern and as we got better known did a few gigs as the opening act for bigger acts. A memorable gig for me was the Rockfurly Shield; three bands from Waikato verses three from Auckland. We played on the back of a semi-trailer with a big outdoor P.A. on a sport Park in Hamilton. The sound was great and I could really feel it. HUP: Who else played in the Rockfurly Shield? Dianne: Other bands from Waikato were Bronze Spirit and Stonehenge, and from Auckland Martial Law, Peking Man and Pleasure Boys. Guest judges were Tony Edwards, who owned the local music shop, Steve Jones, [Radio with Pictures host] Karyn Hay, and Andrew Fagan. Andrew and Steve [were] from the Mockers; we did a couple of gigs with them. HUP: Did you get played on Radio with Pictures? Jeff: No. Karyn showed the album and talked about it but we never did an official video. We did a few things with her and Andrew Fagan when we played with the Mockers. HUP: How would you describe your music? Jeff: Our music was pretty hard to categorise. It was generally described as jazz, punk, cow, folk, reggae, blues, but more recently in the national archive as "Pop" – that’s not my recollection anyway. Radio with Pictures host Karyn Hay had trouble with the fact that what the band recorded didn't represent their live set, which was probably a fair comment. But then again, we felt that the studio was a place for polishing what we had already gigged and it gave us a chance to explore sonic textures and add subtlety to our live voice. That said, we only made it into the studio three times, so we weren't that much of a studio outfit. Live was generally our thing. I was brought up in the islands in the ‘60s so had a reasonable handle of Polynesian rhythms. That, and a fascination with ‘electric’ music in my sister’s record collection made up of the likes of 10CC, The Police and Bob Marley. I was pretty much ripe for the late ‘70s when I tagged along with my sisters to New Zealand bands like Split Enz, Mi-Sex, Th’ Dudes, Hello Sailor and Dragon. My fascination with New Zealand music had begun. HUP: You supported the likes of Netherworld Dancing Toys, The Mockers, The Narcs and Coconut Rough, and played at least a couple of Waikato Orientations. Do you have any favourite gigs or memories among these? Pat: Any gig involving the University was a blast, whether on Campus or at The Hillcrest Tavern. Jeff: Gigs with the likes of Graeme Brazier were a blast. Especially meeting brilliant drummers like Lyn Buchanan; he literally blew me away. Off the back of these we were invited to enter the Waikato Battle of the Bands, and won. So, this got us into the national final in 1984 and after a few heats made it to the final with the likes of The Abel Tasmans, a brilliant Auckland Uni outfit called The Audience, and the eventual winners, You’re a Movie, a spin off from the Hip Singles minus Mr Driver. Their name actually became the title of one of our more poppy songs, penned by Pat. Well we came third equal with The Audience, which was totally unexpected. To win over a hugely partisan Auckland crowd and judges was more-or-less unheard of from a band from the swamp. We actually did a celebration gig with the Audience at [The University of Waikato’s] Oranga, which was an absolute blast, especially the after party. Some of the more memorable gigs were playing with the Netherworld Dancing Toys at the Wailing Bongo after they released ‘For Today’. Man, they were polished and that Annie Crummer, man she had some pipes. I actually know Graeme Cockroft these days and we still chuckle about how natty we were. Touring with Midge Marsden and the Mockers was fun, especially as we had to tear around the country playing these crazy under-age afternoon gigs at places like the Founders Theatre, Baycourt in Tauranga and Mainstreet in Auckland. Kevin started to get us in front of people who were interested in booking us for some of the bigger support gigs, such as the ones you mention. HUP: In 1985 you released an EP called ‘Out of the Swamp’. I take it Hamilton was the inspiration for the title? How did you feel about the album when it was released, and looking back on it now? Jeff: We had been gigging and practicing pretty solidly for three years and finally decided on six songs to record at Harlequin Studios [in Auckland]. This was an extremely sobering experience because you can’t hide from the studio’s infinite focus. We smashed out the rhythm tracks in a night as we could only afford the midnight-dawn rate of I think $35/hr. We had a great engineer Nick Morgan and a musician friend Lawrence Arps to help produce. They helped shape the songs into a more radio friendly format and give some polish to our fairly raw sound. The album met with some favourable reviews. I remember Rip it Up mentioning that we would go down a storm at the Performance Café. Dianne: We recorded the album in Auckland [in a] midnight to dawn session as it was much cheaper. I was a bit star struck when we walked into the studio and [Hello Sailor’s] Harry Lyons was the engineer. I had been to see him play lots of gigs and thought he was a brilliant guitarist and also a nice guy. Our budget was limited, and we would have liked to have spent more time recording and mixing the album. It was our first time in a studio and at the time I was quite pleased with the results. If I listen to it now of course it's very dated, but it's nice to have something on vinyl. And it brings back lots of good memories of those days when we were all dedicated and focused on our dream to get airplay and, I guess, recognition. Pat: The Wetbacks was a charged and driven entity. We rehearsed religiously. We wrote songs and honed all aspects of live performance. Going to Harlequin Studios to record the EP was a highlight for me, but everything was amazing really. Jeff: Listening back to the album now I have mixed feelings. It kind of blows me away that it’s on Spotify. Di’s vocals are still stunning and as a rhythm section we held together well. The song writing seems a little naïve; we did write some great hooks, excepting some flat backing vocals and a really annoying bit in one song that was actually played backward. HUP: Was that an accident on the part of the engineer? Jeff: No, it was my cock up. The last chorus I actually played the kick and snare on ‘1’ rather than ‘&’ (as in 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & etc), which flipped the emphasis. One of those ‘couldn’t fix in the mix’ moments when using two-inch Ampex tape. In Protools today it would be a five-minute fix and no one would be any the wiser. We were young, full of passion, could play, and had a growing following. But the two commercial radio stations in Hamilton flatly refused to support the album, driven by some insane desire to bore the living crap out of their audience by playing the same twenty songs rotated incessantly – well, some things really don’t change do they! So yes, the title refers to Hamilton and the feeling we had at the time that original, alternative music was not appreciated. The lyrics of ‘Entertainment’ kind of points to this. HUP: Was the EP self-released and self-funded? Dianne: Yes we saved everything we earned at gigs, which wasn't much. I think we spent about $2500 on the album. A friend of mine Brian James, who is an artist, did the art work on the album. HUP: You had the song ‘Don’t Get Caught’ - not from the album - included on the 1986 ‘National Student Radio’ compilation ‘Weird Culture, Weird Custom’. That album included the likes of Jean Paul Sartre Experience, Cassandras Ears (featuring Jan Hellriegel) and Battling Strings (featuring David Saunders, later of The 3Ds). How did that opportunity come about? Jeff: We were well supported by Radio Contact at Waikato University, which is where the Weird Custom Weird Culture connection came from. HUP: The last I have found reported for the band is that you left for Melbourne in 1986. Can you tell me what happened to the band from there? Jeff: Not long after we released the EP, Chris took off to Auckland and left the band. We played probably our best ever gig as a three-piece, and I still have a cassette somewhere of us at the Hillcrest that sounds as fresh as the day we played it. But we had been seduced by the sonic textures of the studio and felt we needed another instrument. So, we brought Murray Hintz into the fold on keyboards, to add layers to Di’s guitar and Pat’s increasingly rich bass sound. Dianne: We added a keyboard player to try and broaden our sound, which was very guitar driven. I felt like we needed more colour in the sound. It never really jelled with the keyboards though and we missed Chris's input and style. He and I always complemented each other on guitar. Jeff: More gigs followed, but it started to become apparent that we just weren’t going to break into the New Zealand top echelon, as we didn’t have a record label behind us. We had self-released ‘Out of the Swamp’ and distribution was extremely difficult. We had limited resources in promoting ourselves, and as we were all holding down day jobs something had to give. I got fired from my job at a pub, Pat left Uni, Murray still had the keys to a music store and Di had the only really serious job among us. So we wrote a new batch of songs and decided that New Zealand wasn’t big enough for us. Australia held more promise, or so we thought. One of the highlights was actually our farewell gig at Oranga, where we supported Herbs in front of about 5000 people; it actually felt like WE were the headline and they were supporting us! HUP: 5000 at Oranga? Do you mean 500? Jeff: It sure felt like that many! Dianne: In 1986 I decided to move to Melbourne and the rest of the band followed. Jeff: Arriving in Melbourne in early 1986 was a real ground breaker. This bunch of naïve kiwis coming over the ditch, full of themselves, ready to change the world, soon realised that in the music industry you need more than just raw talent to survive. Things started well enough. My girlfriend at the time was studying sound engineering and introduced us to her lecturers. It just so happened they had a full studio and they needed a house band to record for their senior students to mix. So that’s where ‘Don’t get Caught’ got captured in 48 track glory. Jayrem Records somehow got a hold of it, [and] it ended up on the [Weird Culture Weird Custom] compilation and somehow managed to make it to No 2 on the Alt charts in New Zealand, behind an Aussie band called Boom Crash Opera that we had seen in St Kilda. Gigs were hard to come by in Melbourne and management even harder. The scene in the mid-late ‘80s was more dance oriented synth-pop, sequenced so little need for live drumming and was highly controlled by the clubs. We played a few inner-city places like the Tiger Lounge in Richmond and a couple of pubs in St Kilda and South Melbourne. I went to Jazz school for a while but quit because I thought the teacher was a wanker. Strangely, I’m now playing part time in a band called the Jazz Wankers. Dianne: It was hard starting from scratch again as we had become quite well known in New Zealand, and it was very tough here when we didn't know any bands. That was a thing we missed in New Zealand. We [bands] all knew each other from gigging together and there was a certain comradery between some of the bands we knew. Here [in Australia] it was competitive and we felt isolated. We struggled on, but the joy had gone out of the band for me. We all drifted apart. Jeff: Probably our biggest mistake was flatting together for a year, which brought out personal tensions that we had managed to avoid by living apart in New Zealand. So it was on our way to a Shriekback gig, one of our favourite bands, that Pat told us he was heading home. I remember getting horribly pissed and chundering my guts out in the dunny there as I knew that this was the end. The bond had been broken and after five years, about fifty original songs, one album, a couple of near misses, shitloads of amazing gigs, demos, parties, loves and whisky, it was time to call it a day. As a parting gesture we recorded ‘Fighting for the Right’ at Silkwood and I think someone still has the master somewhere. It would be great to hear that once again; maybe on Spotify perhaps. Pat: Melbourne was a truly humbling experience. So many bands and many of them really good with a range of styles; that was daunting. We were somewhat distracted with getting our lives together in this new environment, and though we practiced regularly, the older songs were getting stale and new material wasn't coming easy like it once did. I found Murray difficult to be creative with, whereas Chris had kinda sparked me. The decision to leave The Wetbacks was excruciating. We had all invested heavily in the band on every level but the new lineup was not the tight bonded unit it was with Chris Corby on guitar and Kevin Oliver on sound (and everything else). That line-up was a family. I returned to New Zealand with my bass guitar, a bag of old clothes and $10. That was late 1986. HUP: Where are you all now? Do you keep in touch, and did any of you continue with music?

Chris: I left Hamilton and the band after 2/3 years to live in Auckland and then across to Melbourne where I have lived for 30 years now. I work as an Audio Director for the Nine Network in Australia mixing TV, documentaries, talk shows or whatever, and continue to Produce and Engineer music for a range of artists in Australia. Dianne: Chris I keep in touch; I am living in the country about an hour and half from Melbourne and haven't played music for many years now. Jeff: After the break-up I played for a couple of Aussie bands of little consequence. Di and Chris and I tried to do something for a while but the magic just wasn’t there, so after recording some demos to help Di on her solo career we called it a day. From there I took up a career in wine, went to Adelaide Uni, got a degree, a proper job, a wife and fathered three sons. I still play music. Not as intensely as back then, but I still try to keep my chops sharp by playing as many genres as I can. We had a bit of fun a while back with a band called Tin Flowers, and did an amazing music/poetry thing called The Blue Moments Project. I play with a Wanaka jazz/funk outfit called Alpine Funk Line, and a grubby pub-rock outfit called Rockhopper, and do the occasional gig for the Nairobi Trio. Then there’s the Queenstown Jazz Festival where I turn into a musical whore-bag and play with anyone and everyone – even Kara Gordon. My boys all play multiple instruments and have all had their own time in bands, so the gene is alive and well in the Sinnott clan. I now live in Tarras in Central Otago with my partner and work as a viticulture and wine consultant as well as owning a part of Ostler Vineyards with my family. I haven’t spoken to the rest of the guys for a few years now; occasionally to Chris and Di on Facebook and lost touch with Pat completely. Pat: I got back into music in late 1988 in Tauranga, which had a thriving scene back then. I have played professionally or semi-professionally since then all over New Zealand and in odd spots in the southern hemisphere. These days I write and record with 'Infinity', an instrumental rock outfit from Hawkes Bay. |

Archives

July 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed